Narrative Essay

For this essay I will be focusing on Narrative and Games Design, inspired by a few games I have played over the years and also by a paper I have read, “Games Design as Narrative Architecture” by Henry Jenkins.

I will discuss how “Narrative” can fit into video games as a medium, give two good and contrasting examples about the marriage of story and gameplay, and talk about narrative in other mediums as I progress.

In Henry Jenkins’ paper, he talks about a debate between ludologists, “who wanted to see the focus shift onto the mechanics of gameplay” and Narratologists “who were interested in studying games alongside other storytelling media”. This got me thinking about two of my favourite games of all time and their totally different approach to storytelling, and how I felt like neither a ludologist, or a narratologist.

Hopefully by the end of the essay you will have a better understanding of some approaches to narrative in video games.

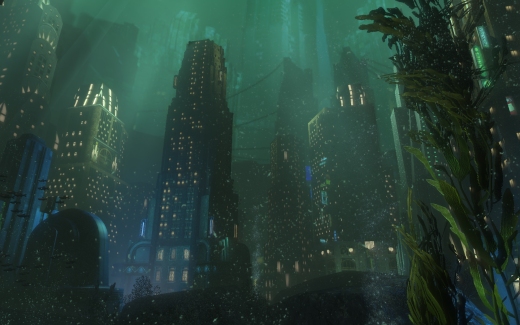

Dark Souls is an action-RPG with what I would describe as a minimalist approach to storytelling. That’s not to say that there’s no story (there’s a lot) but the way in which it is told is very unobtrusive to the player. The storytelling of Dark Souls is a deliberate design choice on the part of the developer, inspired by the Director’s experience as a child:

“Often, he’d reach passages of text he couldn’t understand, and so would allow his imagination to fill in the blanks, using the accompanying illustrations. In this way, he felt he was co-writing the fiction alongside its original author.”

I think this is quite an interesting approach to storytelling in games, as it is what you might describe as an emergent narrative. A small part of it is set and will always happen, but otherwise many aspects of the story only happen as you discover them, and it manages to let the ludologist-inclined have a video game that focuses on gameplay first, but also rewards narratologists for exploring and obsessing over details.

An aspect of games design which works in favour of both ways of thinking is the actual world and environmental storytelling in Dark Souls. In Henry Jenkins’ paper he mentions Don Carson, a former Senior Show Designer for Walt Disney Imagineering, as having said that video games can learn from environmental storytelling techniques that they use on their various theme park rides:

“The story element is infused into the physical space a guest walks or rides through. It is the physical space that does much of the work of conveying the story the designers are trying to tell…armed with their own knowledge of the world…the audience is ripe to be dropped into your adventure. The trick is to play on those memories and expectations to heighten the thrill of venturing into your created universe”

Dark Souls opens with a cutscene that gives you background information on the world, introduces you to a few of the major characters and monsters. It’s pretty much the only time that the game takes control away from the player for any significant period, so if you assume that this is the equivalent of being familiar with Disney characters, every player will at least know this information.

What I think works extremely well in Dark Souls is how you start playing, knowing that “The knights that wear that armour work for “that” guy…” so when you come across one in game you begin to wonder what is their purpose at that spot in the game world? This also goes beyond enemy placement, extending to items you find in the game world, with weapons or armour belonging to characters being deliberately placed, or various healing items being found in appropriate locations.

Internal consistency, an unobtrusive approach to the narrative, and playing on my knowledge of the game world makes Dark Souls almost endlessly fascinating to me. For instance, I can play it for hours and hours, having fun (which is obviously the most important part of a game because if it’s not fun, why play?), but at any point of my own choosing I can look at it from a narratologist’s point of view and ponder about anything from enemy placements to reading item descriptions.

In contrast to Dark Souls, Metal Gear Solid 2 is a game that takes control away from the player an awful lot. If you are reasonably good at stealth games, then for the most part Metal Gear Solid 2 rarely has a gameplay section longer than about half an hour or so before control is taken away from you. Half an hour might sound like a good chunk of gameplay, but control can be taken away from two or three minutes and up to half an hour or more.

My point is that Metal Gear Solid 2’s storytelling and narrative techniques are in stark contrast to Dark Souls, and the method suggested by Don Carson. The storytelling is incredibly obtrusive to the player’s experience, there is little “set dressing” and the tone of the story is utterly bizarre and all over the place.

However, there is a reason I have included Metal Gear Solid 2 as an example in this essay is “why” it tells its story. The game presents itself as the hero fighting to save hostages, including the President, from a terrorist group are being manipulated by a shadowy cabal who wield enough power to order entire nations around. That is the general idea you are presented with for about half the game, until it starts to reveal its true intentions.

AIs have been ever-present throughout the game, but it’s not until the later stages that it’s revealed the “evil” AIs purpose is to control information by bombarding people with so much information (a prophetic critique of 24-hour news and social media) that they can’t discern truth from fiction. The AI also begins to talk to the player directly, saying that they’ve been playing the game for a long time and it’s time to turn it off, and chastises them for potentially mowing down dozens of enemies that you were “told” were the bad guys.

While the narrative techniques used by Metal Gear Solid 2 remain the same throughout the entire game, it’s story is one that changes quite a bit, and to my mind with the nature of information manipulation etc and how characters break the fourth wall and talk to the player, it could only be told in a video game.

When I read Henry Jenkins’ paper, my mind was immediately drawn to Dark Souls and Metal Gear Solid 2 as I felt as if they would make good and contrasting examples as both has opposing approaches to their storytelling. If Dark Souls is a game that would satisfy both narratologists and ludologists, then I think Metal Gear Solid 2 is a game that could possibly satisfy neither. Its gameplay is possibly too interrupted for ludologists (although I find it very fun), and its narrative might be too convoluted for narratologists.

What I found especially curious is that despite Dark Souls being a game for ludologists and narratologists, it’s narrative was one that could be told in other media such as a book or TV show. Metal Gear Solid 2 on the other hand is a story that could only be told in a video game as reading about characters, or watching characters be manipulated by a third party would feel like something out of The X Files or an episode of 24. As a video game, where you have controlled the movements of the characters, you’ve explored environments and every kill you’ve made has been entirely your decision, the story of Metal Gear Solid 2 couldn’t really be told in another medium as effectively.

When we were given the task of writing this essay, I read a few papers and had a few examples in mind, but while researching and writing the essay I have concluded: I don’t think that there is a question about whether narrative belongs in video games, but video games as a medium have a unique problem and solution. Whether you are a narratologist or a ludologist there will be dozens, if not hundreds, of video games that are for you, and many of those stories could be told in other mediums and many could only be told in interactive form.

I think that video games are a melting pot of narrative techniques, where film and books are limited by their form, a video game has the potential to tell a story in a similar fashion but with the addition of being interactive. To some video games have yet to tell a narrative that “works”, and to others they will have experience dozens of games that tell a myriad of compelling stories.

In the end, I suspect that is what narrative in video games will always be, expressions of individuality on the part of developers that sometimes works, sometimes doesn’t, and probably has no definitive answer about what would or would not work.

By John Reid

References

Carson, D. (2003). Environmental Storytelling: Creating Immersive 3D Worlds Using Lessons Learned From The Theme Park Industry. [online] Gamasutra.com. Available at: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131594/environmental_storytelling_.php [Accessed 19 Feb. 2017].

Jenkins, H. (2005). Games Design As Narrative Architecture.

Parkin, S. (2015). Bloodborne creator Hidetaka Miyazaki: ‘I didn’t have a dream. I wasn’t ambitious’. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/mar/31/bloodborne-dark-souls-creator-hidetaka-miyazaki-interview [Accessed 19 Feb. 2017].